COSA DÀ "VITA" ALLA MUSICA? - PARTE II

- Bel Esprit

- 12 dic 2021

- Tempo di lettura: 12 min

Di Carlo Tosato

Tempo e Percezione

In te, o anima mia, misuro il tempo

Agostino di Ippona, Confessioni, XI, 35-37

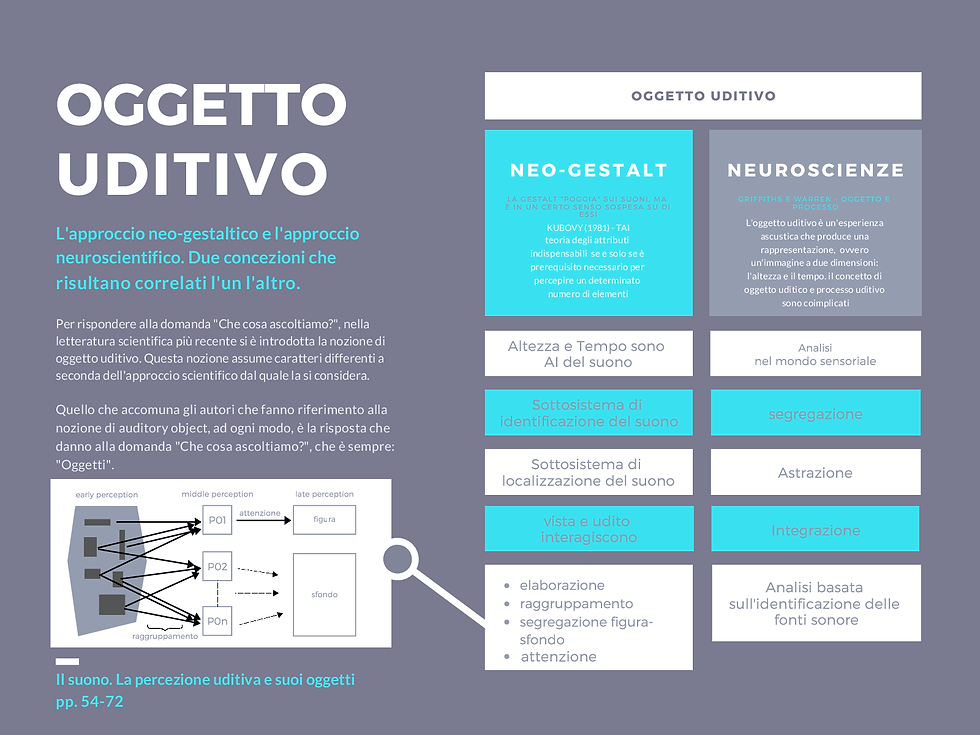

Nell’articolo precedente, in una breve frase che potrebbe sembrare di poco conto ma che invece è fondamentale, dicevo che uno dei due attributi indispensabili di un oggetto sonoro, e quindi anche della musica, è il tempo, oltre all'altezza. Di Bona e Santarcangelo (2018), nel provare come funziona il nostro udito attraverso il tempo, hanno confermato una cosa che ad alcuni può sembrare ovvia, ma che tanto ovvia non è. Cosa accade effettivamente quando noi percepiamo un suono? Quanto può essere misterioso il processo attraverso cui noi udiamo il mondo? A mostrarci l’incredibile complessità dell’udito vi è Albert Bregman, psicologo dell’udito tra i più autorevoli degli ultimi trent'anni, di cui cito testualmente la sua riuscitissima metafora:

"Immagina di essere sulla riva di un lago e che un tuo amico ti sfidi a fare un gioco. [...] Il tuo amico scava due stretti canali a partire da una sponda del lago. Ciascuno di essi è lungo pochi metri e largo pochi centimetri; distano pochi metri l’uno dall'altro. A metà di ogni canale, il tuo amico stende un fazzoletto legandolo alle rive del canale. Quando le onde raggiungono la riva del lago, si propagano fino ai canali e mettono in movimento i due fazzoletti. Ti è permesso solo di guardare i fazzoletti e di rispondere, basandoti sul loro movimento, alle seguenti domande: quante barche ci sono nel lago e dove si trovano? Qual è la più grande? Qual è la più vicina? Il vento sta soffiando? È caduto all'improvviso un oggetto voluminoso nel lago? Sembra impossibile risolvere questo problema, ma si tratta di una buona metafora per descrivere il problema affrontato dal nostro sistema uditivo. Il lago rappresenta il lago d’aria che ci circonda. I due canali sono i due canali uditivi e fazzoletti sono i nostri timpani. L’unica informazione di cui dispone il nostro sistema uditivo [...] sono le vibrazioni dei due timpani. Eppure, il sistema sembra essere capace di rispondere a domande molto simili a quelle formulate sulla riva del lago: quante persone stanno parlando? Chi parla più forte o più da vicino? Si sente il ronzio di un motore in sottofondo?"

(A. S. Bregman, Auditory Scene Analysis. The Perceptual Organization of Sound, MIT Press, 1990, pp. 5-6)

Come si può ben intuire quindi, le problematiche sollevate dal nostro senso uditivo sono molte di più di quelle che ci si aspetterebbe, e il testo di Di Bona e Santarcangelo dà un’ottima panoramica di come la ricerca sta ancora oggi cercando delle risposte. In questo articolo mi soffermerò soltanto su un punto, dedotto dalla lettura di questo libro, che ho trovato particolarmente utile per poi proseguire attraverso altre tematiche e altri autori:

Il modo attraverso cui noi percepiamo il mondo è unico e diverso per ogni individuo. Anche questa sembrerebbe una frase generica e priva di valore, ma vorrei che poneste attenzione al verbo che ho usato. Esatto: percepire. La parola “percezione” ha acquistato negli ultimi decenni un peso sempre più grande nel campo della ricerca. Questa parola contiene in sé un numero esorbitante di implicazioni: vuol dire che noi non vediamo il mondo per come è, ma siamo noi stessi ad essere il filtro tra quello che c’è fuori e quello che sentiamo dentro; vuol dire che già nell'atto di sentire il mondo noi applichiamo delle scelte, decidiamo se focalizzarci su un determinato fenomeno o meno; vuol dire che ad ogni rappresentazione sensibile applichiamo la nostra palette emotiva, creando così ricordi estremamente personali (e badate bene che ciascuna palette contiene esattamente gli stessi colori primari, o le stesse emozioni primarie, di tutte le altre, ma il modo in cui poi si mischiano dipende dalla nostra singolare individualità e dai suoi legami con il mondo esterno).

Noi, attraverso la percezione, creiamo quindi continuamente dei modelli che rappresentano noi stessi, noi in relazione al mondo, e il mondo in sé, e che cos'è un modello se non un’idealizzazione rappresentativa estremamente dinamica, che cambia con lo scorrere del tempo? La psicologia della Gestalt (parola tedesca per forma, modello) asserisce proprio questo, in una maniera più complessa e sfaccettata di come l’ho introdotta io. Anche per gli oggetti uditivi accade lo stesso, e ancora di più per la musica.

Nel caso del suono, le rappresentazioni mentali che ci creiamo sono per lo più a due dimensioni, ma tali dimensioni sono l’altezza e il tempo. Entrambe rispondono alla domanda “dove?” ma in maniera diversa: l’altezza indica la posizione del suono all'interno dello spettro sonoro che siamo in grado di riconoscere (in media dai 20Hz ai 20000Hz); il tempo, estremamente più difficile da definire, indica in principio la posizione nella linea temporale di un oggetto uditivo, ma le informazioni che può trasmettere sono molte di più. Attraverso il tempo sappiamo riconoscere se una serie di suoni è organizzata in modelli riconoscibili, che si ripetono o si alternato, possiamo stabilire se tali serie hanno un meta-messaggio oppure no, possiamo giudicarle “tristi”, “vivaci”, “frenetiche”, “imperiose”, “malinconiche”. Il tempo può essere velocità, densità, dinamicità o caoticità, per esempio.

Ho trovato straordinariamente sorprendente questa definizione di rappresentazione uditiva, non appena mi sono cimentato nella lettura di un altro articolo contenuto in questo caso in Handbook of Music and Emotion, pubblicato nel 2010 dalla Oxford University Press. La funzione della struttura nell’espressione musicale delle emozioni di Alf Gabrielsson and Erik Lindström offre un quadro molto illuminante della diversa importanza dei diversi elementi costitutivi della musica (velocità, armonia, modo, tempo, densità ecc.) ricavato da numerosi esperimenti precedenti.

Ciò che mi ha colpito fin da subito è che si sia appurato che il tempo sia l’elemento più importante che ci permette di distinguere il carattere di un pezzo, ancora di più rispetto al modo (maggiore, minore, ecc.). Sono due gli esperimenti che voglio citare in questo articolo riguardo quanto appena scritto:

Il primo, avvenuto nel lontano 1928 ad opera di C. P. Heinlein, dove a trenta soggetti vennero fatti ascoltare degli accordi, singoli, estrapolati da ogni contesto. Accordi di diverso tipo, che dovrebbero corrispondere a precisi stati d’animo secondo la convenzione musicale tradizionale. I risultati hanno confermato l’esatto opposto: solo due dei trenta soggetti hanno risposto “correttamente”. C’erano risposte emotive “tristi” ad accordi maggiori e risposte emotive “felici” ad accordi minori.

Il secondo articolo, scritto a quattro mani da L. Gagnon e I. Peretz, avvenuto nel più recente 2003, mette a confronto modo e tempo per capire quale sia il fattore più influente nel percepire il carattere emotivo di un pezzo. Ne è venuto fuori che entrambi sono essenziali per l’espressione percepita, ma il tempo lo è in misura maggiore.

La musica quindi, più che l’arte del suono in sé, sembra essere piuttosto l’arte del tempo, e del suono in relazione al tempo. Ma di quale tempo stiamo parlando? Del tempo realmente esistente, sempre che esista, del tempo che la nostra mente percepisce, o dei modelli temporali già insiti nella nostra mente e attraverso cui il nostro cervello opera?

Agostino fu uno dei primi ad intuire la soggettività del tempo, e quanto importanti siamo noi stessi a crearlo. Scrisse “In te, o anima mia, misuro il tempo”. Oggi queste intuizioni stanno ottenendo sempre più riscontri nella ricerca, rivelando un mondo, il cervello, che opera in maniera molto più plastica e dinamica di quanto si pensasse prima e, a volte, di quanto si continui a pensare ora.

“La nostra esperienza del tempo non è un’ombra in una caverna che nasconde una qualche verità assoluta; il tempo è la nostra percezione” (Alan Burdick, 2017).

Ho il vago sentore che se la musica continua ad essere un grande mistero ancora oggi, è perché quest’arte è diretta manifestazione della nostra essenza temporale, e il tempo a sua volta rimane tuttora incompreso nella sua interezza. Possiamo trovare migliaia di definizioni di “tempo”, ognuna ugualmente valida, possiamo scoprirla attraverso domande più strane e originali, ma è come se la sua essenza ci sfuggisse sempre di mano, esattamente come quando cerchiamo di rincorrere un arcobaleno.

Tempo e percezione, questo era il tema di questo articolo. Li reputo elementi centrali alla comprensione della musica, nella sua vitalità e umanità. Nel prossimo articolo riprenderò questi concetti, ma porterò il discorso verso un altro grande elemento, tra i più bistrattati nella musica ma anche nella ricerca nel secolo scorso: le emozioni. Importantissime porte di accesso all'uomo, fondamentali anche nei nostri processi razionali, al mantenimento omeostatico del nostro organismo e, a mio ponderato e documentato parere, elementi imprescindibili nella musica in quanto manifestazione umana e naturale, che andranno a spiegare l’alessitimia di buona parte della musica d’avanguardia di questi due secoli, enormemente stratificata da elementi intellettuali completamente inadatti ad essere trasmessi attraverso i suoni, o al sentire in generale.

Bibliografia di Riferimento Di Bona E., Santarcangelo V., Il Suono. L’esperienza Uditiva e I suoi Oggetti, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milano, 2018 Gabrielsson A., Lindström E., The Role of Structure in the Musical Expression of Emotions in: Handbook of Music and Emotions, curato da P. N. Juslin e J. Sloboda, Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 369-400 Burdick A., Perché il Tempo Vola. E perché la felicità è un lampo e quando ci annoiamo le ore non passano mai, trad. Di Gledis Cinque, Il Saggiatore, Milano, 2018

Libri Consigliati Baldi G., Cronodiànoia o del Realismo Interiore. Pensiero e Sentimento del Tempo. Proposte per la Musica del XXI secolo, Armelin Musica, Padova, 2015

WHAT MAKES MUSIC “ALIVE”? - PART II

Time and Perception

In you, O my mind, I measure times.

Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, XI, 35-37

In the previous article I wrote, there’s one little fact that may have been escaped from your attention, since I have dedicated to this fact just a single line: besides pitch, time is one of the most important attributes of any auditory object. Di Bona e Santarcangelo (2018), while trying to explain how hearing deals with time, they confirmed a fact that might seem obvious but actually it’s really important. But first let’s take a glance to the questions which have brought to the answer. What happens actually when we perceive sound? How mysterious the process which makes us hearing the world can be? They seem not so difficult though; maybe Albert Bregman, one of the most influential hearing psychologist in the last 30 years, could make us really feel the breadth and complexity of these questions with this little metaphor:

"Imagine that you are on the edge of a lake and a friend challenges you to play a game. The game is this: Your friend digs two narrow channels up from the side of the lake. Each is a few feet long and a few inches wide and they are spaced a few feet apart. Halfway up each one, your friend stretches a handkerchief and fastens it to the sides of the channel. As waves reach the side of the lake they travel up the channels and cause the two handkerchiefs to go into motion. You are allowed to look only at the handkerchiefs and from their motions to answer a series of questions: How many boats are there on the lake and where are they? Which is the most powerful one? Which one is closer? Is the wind blowing? Has any large object been dropped suddenly into the lake?

Solving this problem seems impossible, but it is a strict analogy to the problem faced by our auditory systems. The lake represents the lake of air that surrounds us. The two channels are our two ear canals, and the handkerchiefs are our ear drums. The only information that the auditory system has available to it, or ever will have, is the vibrations of these two ear drums. Yet it seems to be able to answer questions very like the ones that were asked by the side of the lake: How many people are talking? Which one is louder, or closer? Is there a machine humming in the background? We are not surprised when our sense of hearing succeeds in answering these questions any more than we are when our eye, looking at the handkerchiefs, fails."

(A. S. Bregman, Auditory Scene Analysis. The Perceptual Organization of Sound, MIT Press, 1990, pp. 5-6)

As we can clearly guess then, our hearing raises far more questions than we would actually expect, and Di Bona’s & Santarcangelo’s book gives us an optimal overview about how hard today’s research are still seeking answers. In this article I will dwell on one detail, came up after reading the book mentioned in this paragraph, which is particularly useful in order to get later to other topics and authors:

The way by which we perceive world is unique and different for each individual. This sentence might seem as well too generic and pointless, but I would like you to focus on the verb I used there. Exactly: perceive. Perception became increasingly important in the last decades within research. The amount of implications that this word gives us is incredible: it means that we don’t see the world as it really is, but we ourselves are the filter which makes what we feel different from what there’s really out ourselves; it means that in our perceiving the outer world we are already making choices, deciding on which phenomena we want to focus more; it means that to whatever sensitive representation we are building we are applying our emotive-palette, creating thus extremely personal memories (and bear in mind that each emotive-palette contains exactly the same primary colors, that is, primary emotions. What differentiate them is the way in which we combine them and relate them to the outer world).

Throughout perception we are continuously creating mental configurations representing ourselves, our relation to external things and the world itself. And what is a mental configuration but an extremely-dynamic representative-idealization which continuously changes as time goes on? Gestalt psychology (german term for form, pattern or configuration) affirms right what is written above, of course in a more complex and multi-faceted way as I introduced that. For auditory objects it happens the same, especially when we are diving into music-related phenomena.

Concerning sound, the mental configurations we create upon it are mainly based on two dimensions, but those dimensions are pitch and time. Both of these answer to the question “Where?” but in different ways: pitch indicates sound (i.e. auditory objects) position within the sound spectrum we humans are able to recognize (generally from 20Hz till 20000Hz); time on the other hand indicates at first the position of an auditory object within a timeline, but it’s extremely difficult to give unambiguous definition to it, since there’s a lot more informations which time comes with. Through time we can define if a number of sounds is organized in recognizable patterns, which repeat or alternate themselves; we can establish if these patterns convey meta-messages or not, we can consider them “sad”, “lively”, “frenetic”, “majestic”, “nostalgic” and so on. Time might be both speed, density, dynamism or chaos, for instance.

I found later on this definition of auditory representation extremely remarkable, once I read another article included in another book, Handbook of Music and Emotions, published in 2010 by Oxford University Press. The Role of Structure in the Musical Expression of Emotions by Aalf Gabrielsson and Erik Lindström offers an eye-opening insight about diverse importance of different building blocks for music (speed, harmony, tonality, time, density, ecc.) obtained from the observation of numerous previous experiments.

What has struck me since the beginning was the fact that time is the most important element which makes us able to distinguish different musical characters, way more than tonality (major, minor, ecc.). I mention now two experiments reported in the article above which show better the point:

The first one, which took place back in 1928 made by C. P. Heinlein, 30 people were supposed to listen to different chords, out of any context. Different kind of chords which, according to traditional music conventions, should address to specific moods/states of mind. The results overturned expectations: only two of thirty people answered “correctly”. There were “sad” feedbacks to major chords and “happy” ones to minor chords.

In the second experiment, happened in the more recent 2003, written by L. Gagnon and I. Peretz, time and tonality are compared again in order to understand which one is actually affecting our perception of music and its emotive states. It came out that both are essential for our overall perception, but time is to a greater extent the most essential.

Therefore music, despite being only sound-based art, seems more like time-based art, and art of sound related to time. But which kind of time are we talking about? Are we talking about time in its real existence (assuming it exists at all), the time we are perceiving, or about time-configurations already present in our mind and with which our Self being operates?

Saint Augustine was one of the first who recognized that time was more subjective rather than objective, and how important are we to create it. He wrote “In you, O my mind, I measure times”. These intuitions are nowadays more and more confirmed by research, revealing a world, our brain, which works more practically and dynamically than how we thought before and, sometimes, more than we are still thinking.

“Our experience of time is not a shadow in a cave hiding some absolute truth; time is our perception” (Alan Burdick, 2017).

I have a sneaking suspicion that if music is still today a great mystery, that’s because it is direct manifestation of our temporal essence, and time in turn is still nowadays a great mystery. We could find thousands definitions for “time” and each of them will be equally valid. We could ask more and more specific questions, but time’s pure essence seems to escape always from our understanding, like when we are trying to chase the rainbow.

Time and its perception, that was the topic of this article. I consider them as cornerstones in understanding music, in its vitality and humanity. In the next article I will resume these concepts, but I will bring the discourse to another great cornerstone, which in the past century was heavily mistreated both in music and research: emotions. The greatest gateways for humankind, essential also in our rational thoughts, for our homeostatic balance and, in my own really personal opinion, crucial elements for music as human and natural manifestation. The next article will try also to explain the alexithymia of most of the avant-garde music in the last two centuries, music stratified by intellectual elements which are unsuitable to be transmitted through sounds, or to be listened in general.

References

Di Bona E., Santarcangelo V., Il Suono. L’esperienza Uditiva e I suoi Oggetti, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milano, 2018

Gabrielsson A., Lindström E., The Role of Structure in the Musical Expression of Emotions in: Handbook of Music and Emotions, edited by P. N. Juslin e J. Sloboda, Oxford University Press, 2010, pg. 369-400

Burdick A., Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation, Simon & Schuster, 2017

Suggested books

Baldi G., Cronodiànoia o del Realismo Interiore. Pensiero e Sentimento del Tempo. Proposte per la Musica del XXI secolo, Armelin Musica, Padova, 2015 (ITA/ENG)